The White Wing - Aerodrome 2

Following the crash of the Red Wing, the members of the Aerial Experiment Association understood fully the problems posed by a lack of lateral stability in flying machines. A great deal of discussion and problem solving ensued on how they would overcome this problem in their next aerodrome.

The solution settled upon was one originally proposed to the associates in a letter from Dr. Bell who was attending to business in Washington.

Bell suggested the addition of an 'aileron' to the tip of each of the wings. McCurdy described it as follows, it was "...simply a flat flap mounted at each wing tip, and these were attached to the body of the pilot by a harness...".1 Aileron is a French word for little wing and it was originally named by the pioneering French aviators Robert Esnault-Pelterie and Henry Farnan who are credited with simultaneously developing the control device along with the AEA.

The inclusion of the aileron for lateral control was one of the most significant advances in the development of aviation. The Aerial Experiment Association applied for and was granted a patent for the device.

Casey Baldwin was selected as the lead designer of the second aerodrome. As was now customary with the associates, the lead designer was in charge of drafting the plans for the craft and making final decisions after problem solving discussions were concluded.

The second aerodrome was christened the White Wing, after the white nainsook cloth used to cover the wings. Since the weather had turned to spring conditions, the White Wing would have to take off from land so a tricycle landing gear, using wheels from the Curtiss motorcycle operations, was developed.

The manufacture of the plane was under the supervision of William F. Bedwin of Baddeck. Bedwin had been brought to Hammondsport to assist with the work. He had a great deal of experience in building Dr. Bell's large kites as he had been the supervisor of the kite operations in Baddeck.2

By mid-May of 1908, following two months of construction, the White Wing was completed. A horse racing track owned by a Hammondsport wine maker in nearby Pleasant Valley was selected as the location to test fly the aerodrome.

This aircraft was much sturdier than the first aerodrome. The White Wing was also a single seat, single engine aircraft. It was powered with a new Curtiss air cooled engine especially designed to be lighter in weight while still producing 40hp of thrust. The fuselage length was 6.1metres (26ft 3in) and the wing span was 7.44 metres (43ft 3in). Again, bamboo and hand shaped spruce were used to make the frame of the aerodrome. The aircraft was much stronger and better braced with crossing guy wires that made it much sturdier than the Red Wing.

In its first few attempts at flight, the White Wing did not get into the air. Curtiss wrote "Great was our surprise, however, when it refused absolutely to make even an encouraging jump. For a time we were at a loss to understand it. Then the reason became plain as day; we had used cotton to cover the planes, and, being so porous, it would not furnish the sustaining power in flight."2

To counteract the lack of lift caused by the porous wing coverings, the associates coated the nainsook wing covering with varnish making it impervious to air and greatly increasing the capacity of the wings to raise the aerodrome.

On the taxi runs that had demonstrated the lack of lift in the wings, the associates also noted that the tricycle gear under the fuselage was not strong enough for the bumpy ground. They strengthend that as well while they were solving the problem of the porous wings.

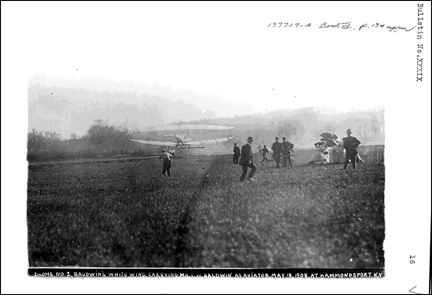

On Monday afternoon, May 18, 1908 the White Wing was again ready for trial. With Casey Baldwin as pilot the White Wing took to the air on the first attempt of the day.

After taxiing 150 feet the White Wing lifted off. Baldwin's flight reached an altitude of ten feet and the aerodrome flew for a distance of 45 metres (134 ft) before the wheels briefly touched the ground and then lifted again. Baldwin brought the White Wing down after a total of 204 metres was covered.3 Douglas McCurdy captured the flight in photographs for the Association's records.

On May 21st Glenn Curtiss was in the pilot's seat for his first ever flight. He kept the White Wing in the air for 310 metres (1017 ft) before successfully landing.

On May 23rd it was McCurdy's turn to fly. He lifted the White Wing to an altitude of twenty feet and covered 182 metres when, on attempting a landing, the right wing hit the ground and the aerodrome crashed in a cloud of dust. McCurdy was thrown from the aircraft and was bruised by the fall. Writing later in the official record of the Association, the AEA Bulletin, McCurdy stated that had felt totally in control during the flight and as he started to descend. Then, he said, "...a puff of wind..." upended the aerodrome and sent it careening into the ground.4

The wings and fuselage were badly damaged, but the motor was salvaged. It was decided to scrap the White Wing and begin the construction of aerodrome number three.

Notes:

- Green, H. Gordon. The Silver Dart. p.44.

- Curtiss, Glenn H., and Augustus Post. The Curtiss Aviation Book. p.45.

- New York Herald, "Baldwin's "White Wing" In The Air: A Triumph in Aeronautics. There is some discrepancy between the distance of 93 yards of overall flight distance reported in the Herald on May 20, 1908 from a telegram sent by the Dr. Bell on behalf of the AEA and other accounts that show a greater distance recorded by Dr. Bell in the Bulletin of the Aerial Experiment Association.

- Green, H. Gordon. The Silver Dart. p.48.

References:

- "Baldwin's White Wing in the Air-A Triumph in Aeronautics." The New York Herald, May 20, 1908. Page 3.

- Curtiss, Glenn H., and Augustus Post. The Curtiss Aviation Book. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1912. 1-307

- Green, H. Gordon. The Silver Dart. 1st ed. Fredricton, N.B.: Brunswick P Ltd., 1959. 1-208

- House, Kirk W. Hell-rider to King of the Air - Glenn Curtiss's life of innovation. 1st Ed. ed. Warrendale, Pa: SAE International, 2003. 1-273.

- Roseberry, Cecil R. Glenn Curtiss: pioneer of flight. 1st ed. ed. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1972.

- Shulman, Seth. Unlocking the Sky Glenn Hammond Curtiss and the race to invent the airplane. 1st ed. ed. New York: HarperCollins, 2002. 1-258.

Note: Photos of the White Wing are from the Bulletin of the Aerial Experiment Association, courtesy of the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum. No further publication or distribution is authorized without the expressed permission of the Museum.